Written by Sheana Ochoa

Written by Sheana Ochoa

Adding new dimensions to our understanding of an American cultural icon, Susan Mizruchi’s new biography on Marlon Brando dispenses his reputation as a womanizing glutton with a portrait of a man whose insatiability for reading and learning rivaled that of any of his other appetites. During six years of dogged research and writing, the biographer reassembled Brando’s extensive collection of over 4,000 books that had been auctioned off after his death and ended up as far as a Jewish collector’s library in Russia, and in the home of Brando’s friend, Johnny Depp, who bought the collection of 1,000 books on Native Americans that Mizruchi assesses surmounts the libraries of any academics in the field. By studying the copious marginalia that Brando left in his often-misspelled scrawl, Mizruchi uncovers a man driven to understand and build the characters he portrayed, while also studying the politics, philosophy, law, government, ecology and culture of both eastern and western society. Here we come to know the thought behind the choices Brando made in his career as one of the greatest actors of our time and throughout half a century of social activism.

Brando’s appreciation for reading and interest in social justice began at home, but blossomed when Brando met Stella Adler at the age of 19. Adler told Brando, “All of us have a role in improving the world.” His career in activism started when Adler recommended him for the play “A Flag is Born” to bring awareness to American Jews of the atrocities taking place to their brethren in Europe. By then, Stella had Brando audition for his first Broadway role in “I Remember Mama,” and his subsequent role in “Truckline Café” which put him on the map as a new force in American theater.

Brando came of age during the mid-20th century, when acting had finally evolved from its demonstrative Roman-Greco origins to a discipline that one could actually study, thanks to the father of modern acting theory, Constantin Stanislavski. Stella Adler was the only American acting teacher to have worked with the Russian master. She merged their work together with her own experience growing up on the Yiddish stage. Adler honed an approach to acting that was ideal for young Brando who was thirsting for knowledge and culture. As Mizruchi observes, “’Some moments in his [Brando’s] films seem filmic realizations of her classes. Consider Adler lecturing on hats: ‘The person who wears a high hat has to know how it lives… Do you know you have to use both hands to put it on? It’s made to be worn straight. The person who wears it has a controlled speech, a controlled walk, a controlled mind.’ Now, go watch how Brando, as the aristocrat ship’s officer Fletcher Christian, puts on his hat in the first scene of Mutiny on the Bounty.”

As the first biographer of Adler, I couldn’t resist asking Mizruchi what she thought might have happened had Brando never met Stella. An effusive interviewee due to her passion for her subject, this question at first stumped Mizruchi, but her response couldn’t have been more pitch perfect. She mentioned the role of “serendipity in people’s careers,” pointing out how Brando would not have tolerated the studio system and its contractual restrictions had he arrived in Hollywood prior to its dismantling. His temperament required some semblance of freedom. By the same token, he found the ideal teacher in Stella Adler. “Yes,” Mizruchi pondered, “he could have possibly been discovered by someone else,” but more importantly Adler took Brando under her wing, bringing him into her home and offering a “familial repurposing” to what had been a tumultuous childhood. She was a mother figure as well as a mentor who gave Brando the tools to flower. Hypothesizing whether Brando would have become Brando without meeting Stella is akin to postulating where acting craft would be today had Stella never met Stanislavski. Adler disseminated the Russian technician to generations of actors, while Brando executed her teachings into tangible, three-dimensional characters, setting the standard for every actor in his wake.

The world was ready for Brando.

Both Brando and Adler recoiled from the term “method acting” because it didn’t speak to the research-based acting that Adler taught was vital to conveying a work’s universal themes to the audience. Only through studying the social, political, economic and geographic background and specific upbringing of a character could an actor understand a role well enough to truthfully render its humanity to audiences. Each character has his own body language, rhythm of speech and facial expressions. His clothes or the items he touches from a coin to a pipe are handled in a manner unique to that individual. “Every object you bring on stage,” Mizruchi quotes Adler, “has to tell you about the circumstances of the character you’re playing and the world in which he lives.” With this foundation, Brando instinctively created a personality for each of his roles. He insisted, as Adler would have it, on knowing the motivation behind a character’s action, even if he had to rewrite the script himself. Mizruchi reveals Brando did exactly that in all of his roles, and while it isn’t uncommon for actors to alter their lines, Brando’s editing reflected his acting: Every word, just as every behavior, had to serve the plot or develop the character. Invariably, he ended up excising superfluous lines to get at the heart of the meaning of the work.

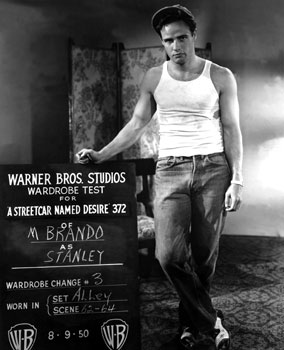

With meticulous research Mizruchi deduces what Brando was reading as he built the true-to-life portraits that allowed audiences to understand the many faces of power (The Godfather), fear (A Streetcar Named Desire), love (Sayonara), and madness (Reflections in a Golden Eye). I asked Mizruchi if the title of her book was meant to conflate Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile with that of Brando’s persona. While appreciating my symbolic extrapolation, Mizruchi explained the “smile” referred to the actor’s mask—one that Brando mastered not only through his varying character’s smiles, but the entire visage of each role he played.

As the oldest profession in the world, that of storytelling, the actor’s mask alludes to the way in which we all “act” in our lives. Brando would go so far as to say “acting” is a means of survival. Isn’t it true that a person has different ways of comporting with his or her boss than with a lover, child, valet, or doctor? The idea that “all the world’s a stage” democratizes the elusive craft we know as acting, which is in keeping with Brando’s democratic principles when it came to social justice. Through storytelling the actor’s mask becomes the vehicle through which human beings construct meaning out of life, one another, and the self.

I often think about how each of the arts have traditions. Writers, painters, and musicians have artistic movements, genres, and pioneers. Actors are different in this aspect, primarily because as I mentioned, acting had hardly evolved since ancient times. Ask an actor about his technique and with rare exception you are told that it’s “instinct” or “a mystery.” Interestingly, while Stella Adler revered acting and insisted on the responsibility of the actor to uphold a 2,000-year-old tradition, Brando is better known for downplaying the profession, as Mizruchi quotes Brando on The Dick Cavett Show in 1973: “It is a business, it’s no more than that, and those who pretend it’s an art I think are misguided. Acting is a craft and it’s a profession not unlike being an electrician or plumber or an economist.”

Yet Mizruchi knows her subject well. She clarifies that Brando’s disparagement of acting came mostly from the way in which Hollywood operates off profit to the detriment of innovation and creativity. She argues how although Brando would say he was “done with acting,” he continued not only to perform till the end of his life, but to invest himself in his characters. As late as 2001, Mizruchi notes how much “acting still mattered to him.” Brando began teaching acting with “global ambitions for these classes, which he planned to film and distribute worldwide.” Ultimately, Brando knew what Adler understood: through stages and screens around the world acting has a universal scope and power to transform lives through story.

Hopefully these two unprecedented biographies, released within two months of each other, Brando’s Smile and Stella! Mother of Modern Acting will earn the art of acting the respect it deserves.

Brando’s Smile, His Life, Thought and Work (W.W. Norton, 2014), by Susan L. Mizruchi

Stella! Mother of Modern Acting (Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, 2014) by Sheana Ochoa

Sheana Ochoa  received a Masters in Professional Writing at the University of Southern California. She has published widely in such outlets as Salon, CNN.com and the Los Angeles Review of Book’s affiliate, The Levantine Review.Ms. Ochoa inaugurated the One-Act Play festival at the Stella Adler Academy where she directed her one-act play, The Masterpiece. In 2012, she became a founding member of Freedom Theater West, co-producing their premier production. Her revival of “Haorld & Stella: Love Letters” won Pick of Fringe at the 2014 Hollywood Fringe Festival. Stella! Mother of Modern Acting is Ochoa’s first book. Follow Sheana on twitter!

received a Masters in Professional Writing at the University of Southern California. She has published widely in such outlets as Salon, CNN.com and the Los Angeles Review of Book’s affiliate, The Levantine Review.Ms. Ochoa inaugurated the One-Act Play festival at the Stella Adler Academy where she directed her one-act play, The Masterpiece. In 2012, she became a founding member of Freedom Theater West, co-producing their premier production. Her revival of “Haorld & Stella: Love Letters” won Pick of Fringe at the 2014 Hollywood Fringe Festival. Stella! Mother of Modern Acting is Ochoa’s first book. Follow Sheana on twitter!