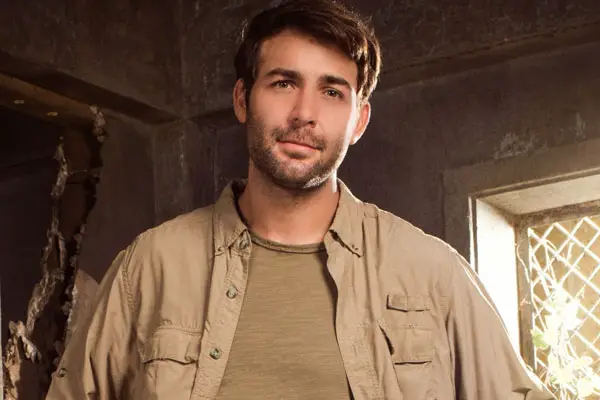

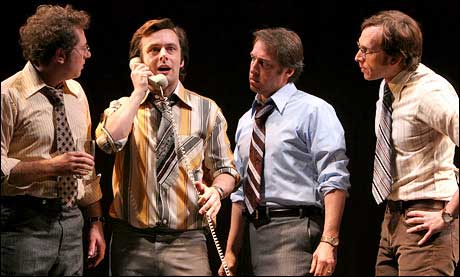

If you got a chance to see the Broadway show, Enron you’ll know that Stephen Kunken was well deserved in getting a Tony nomination for Best Featured Actor in a Play for his role as Andy Fastow.

I say “got a chance” because the day Stephen found out he was nominated he was also told that the show would be closing later that week.

If that were me, I’d want to jump out a window but Stephen is taking it all in stride.

And why shouldn’t he? The critics universally praised his work, he and his wife just adopted a baby and he’s such a fantastic actor, the phone is probably already ringing in his agents office.

I got a chance to talk to him while he was sitting in his car about to take a well deserved break.

Congratulations on your nomination.

Thank you so much.

How did you find out about it?

I was watching, because I knew it was important to find out about the longevity of our show – Enron. With how expensive the show was, if it didn’t get nominated, I knew it would probably be a rough road for us. I was curious and watching for a couple of minutes. Then, they let it go and I watched it online. I sort of saw it all happening in rapid succession. They did the 5 big categories first on TV and then they ended it. So I thought that I had missed my category. I was like, “Damn, I can’t believe it!” But then they actually went back to it.

What’s that feeling like, to be one of the top five actors nominated?

It’s crazy. I don’t know that it’s sunk in yet. I was just talking to my wife about it. It’s such an incredible honor and its a thing that you always dream about as an actor, I think. Especially as a New York theatre actor who grew up on the Tony’s and grew up coming to see Broadway shows. I went to Julliard in the city, which is an institution for theatre.

I remember my first Broadway show, right before I went on, saying “Wow, as soon as the first word comes out of my mouth, I’m going to have done a Broadway show.” It was an incredible, huge threshold to walk across. It hasn’t even really sunk in yet to be considered a part of the community in a performance that was noteworthy in this season of incredible actors and performances. It’s kind of mind-boggling. It’s thrilling. It’s such a huge honor. I know these are all the things that everyone always says, but it’s so true. You actually really do feel awed by the attention and awed by people actually caring. There’s nothing that I just said that’s new or exciting, but it’s totally true. It puts all of that work into perspective for a moment. It’s a milestone in your career that you can look back and you can say, ‘Oh, my God, I actually put together a little body of work.’ It’s quite cool.

Is it true that now you can get better seats in a restaurant?

I don’t know. If I won the award, I could walk in with the statue and I still think I would lose instantly to anyone who’s been on a TV show or in a film. Maybe at Angus McIndoe across the street they might say “Hey!” but I think other than that, that’s the beauty of the theatre that unless you saw it, you don’t really know it.

And then, a couple of hours later, how did you hear about the show closing? That’s got to be a sucker punch.

Well, I saw that the show hadn’t been nominated and the producers were pretty frank with us earlier on. The day after we opened, we had a day off and we came back and talked about it. New York is tough. The New York Times is a such an important paper for a big Broadway show. Because it’s a table setter and a tone setter for the way people think about a show. Ben Brantley from The New York Times really didn’t like the show. He had very nice things to say about me, which was very nice but he didn’t like the show. And already you could feel as we came back that we were battling that perception. We had amazing reviews from all other places, but theater people have very strong opinions about the play. So, I knew from the producers who said the Tony’s would be very important to us. So I knew we were in a bit of a race, and when that didn’t come through, I knew that our time might be short. But I didn’t think it would be that short. We found out that night. They sent us all an email basically saying “Please come to the theatre a half an hour before.” Then they told us that there wasn’t an advance being built and that the Tony’s were really important to help build that advance, and that the show was very expensive, and the timing was wrong, possibly, for a show all about finance. There were a million reasons. You could Monday morning quarterback what happened with it a million different ways but we found out that night that that was going to be our last week, which was crazy.

It was heartbreaking also, because you hit that moment when you’re like, ‘I can get to live in this thing and I can show people my work,’ and then it was gone just as quick. But it’s a great metaphor for the theatre. The theatre is a living organism that is of the here and the now, and it’s going to disappear and that’s the beauty of it.

It’s gotta suck that you put in all this time and energy, and you got nominated for a Tony, and people can’t see your work.

Yeah, it’s definitely a drag. All my out-of-town friends will have missed it. And people I know who bought tickets for later in the summer won’t get to see it. But, in terms of my community of people, a lot of them were great. They rushed to go see it or they had seen it in the preview period. I know that the producers made a valiant attempt to try and get as many of the Tony voters in before the show closed. They got a good bit of those people in.

As far as the joy of doing a play, and getting good notices, and having some kind of acknowledgement that you than get to live in that because it happens so infrequently. That was a drag, definitely.

Let’s go back to the beginning. How did you get your start? When did you realized you wanted to be an actor?

I did it in high school. I did all the school shows. I had a great high school drama professor who really made us cut our teeth in high school, not on Bye Bye Birdie, and stuff like that but on Bertolt Brecht. That really pushed our imaginations. So, I sort of knew when I was in high school that I really loved it. When I went to college, I went as a political science major, actually, and took a couple of classes. I realized in political science, it’s really a science of figuring out people, and how to manipulate people and how to manipulate perception and understand it. It was all these things that I was doing and loving in the arts, but it seemed for more nefarious purposes. So, I decided that I’d rather do it for entertainment and to help people see the world in a different way that to build a political career.

And then you went to Juilliard?

Then I went to Juilliard in the city, which was very lucky.

I talked to Carrie Preston who also went there. She said it was like an acting boot camp. It was like her Vietnam she said.

Totally. I love Carrie Preston, she’s a buddy of mine. She’s awesome. The thing about Juilliard that’s so great, in terms of the hardest part about Juilliard, is that they look at you when you come in, and they say “You do these amazing things naturally. And let’s be honest, you don’t need us to continually tell you over the course of these four years what that is that you do great. So let’s give you as many skills and tricks and craft as we can do over four years with things you’re not good at.” So, you can spend four years thinking you’re not good at all, which I think is the danger if you go there too young or too green. You can start to lose your confidence. But if you can maintain your sense of the world, you can come out of that program with an incredible set of skills, and having worked with some really great people.

You pretty much work non-stop; do you credit your education with that?

Yes, in large part. I think a huge part of why people want to work with you or hire you—it’s 50% what you’re doing in the auditions and how prepared you are and what kind of take you have on a role, but the other 50% is, are you somebody who’s reliable and that people want to work with. That starts to snowball. I pride myself on being somebody whose prepared and who isn’t causing problems when they’re in rehearsal and is just really there to make the play better, to make the project better. I think that’s an important part of why you continually work or don’t work. Your reputation precedes you into a room. Hopefully, it’s working for you as opposed to against you.

You’ve played two real people; Jim Reston in Frost/Nixon and Andy Fastow in Enron. They’re completely different shows, but was the research on the people the same for you?

Yes, in a way. It’s interesting, when you play a non-fictional character; you’re playing somebody who you can pull lots of source material for. It’s exciting because a big part of your job is done. You can see pictures of that person, you can hear that person, and you can do a lot of the external work that will get you close to that person. But then there’s a point when that stops being helpful, and you have to do the same work you would do as an actor on any fictional character. Which is go to the script and figure out exactly what the author or playwright is asking you to do. Because, even if I did the greatest Jim Reston ever, but it was running counter-intuitive to Peter Morgan’s script, then we’re in conflict with each other. So, it’s more important that I know what David Frost is saying about Jim Reston in the play and then somehow interpret that either to embody that or do the opposite of it. To take all the given circumstances that I know from the world of the play and try to marry them with some of the things I know. It is a kind of hybrid thing when you work on a non-fictional character, but it’s not a far afield from just working on Chekhov. Where you’re completely creating a character from scratch. You have to do all that same beat to beat, moment to moment work, or else we would just be doing documentaries, essentially.

So when you get a new script—and I know you’ve done a lot of new plays— what are the very first things you look for and you do?

That’s a great question. I think I probably start off reading the script a number of times. I had a professor once who said that your first impression is so important, and that when you read a play the first time, don’t read it piecemeal, don’t read it on the subway, 10 pages here, another 15 pages there. You’re first impression of it should be in some ways the same as if you were to sit in a darkened theatre and watched 2 hours of a play. So that impression is really important. The first time through, I’m really just responding emotionally or intellectually to the experience. And then I go back and read it a few more times, because it’s actually really interesting to read a play before you know who you’re playing in it. Sometimes, if you get the breakdowns and there’s equal parts that you might be right for, it’s really interesting to read a play not tracking it for your character. You sometimes learn a lot in that respect. Once you’ve read it the first time or you know who you’re playing, I start pulling out all the things I know, trying to develop the skeleton of a character from all the bread crumbs that the playwright has left you. Very simple things, like how old the person is, where the person grew up, to all the emotional things about that person; what are their triggers? What are the things that set that person off? All of the things we work on in acting school, like what does this person want? What does this person out of life? And then you start to go back and filter all of that together and I find there comes a point where you’re never even learning the lines, because you’re doing so much work on figuring out why the lines are there that it sort of figures itself out.

I know that you just adopted a baby, are you going to take some time off and hang out with the family or are you calling your agent and saying “Let’s get back to work”?

It’s funny you say that, because my wife and I have a little house up in Connecticut. I’m literally sitting right now in a car in the driveway. We just got here, battling traffic. I was doing this play David Cromer’s Our Town, I was playing the stage manager right before we started rehearsals for [Enron]. Literally, I left Our Town on a Thursday night, did my last performance. On Friday, we flew off to Ethiopia, to get our daughter. We spent two weeks in Ethiopia, flew back and landed on a Saturday night and started rehearsal on a Monday. So it’s been brutal. But she’s absolutely the greatest kid in the world. She is the easiest, sweetest, most grounded kid who’s kept all this in perspective, all the things like the show closing. I have this little face to come home to who doesn’t care about any of that, it’s amazing. Part of closing is going to be lovely. I’ll get to spend a chunk of time with her. Certainly I love working, I love what I do, and if opportunities come up, I’m sure I will be on the horn with the agents saying “What’s next?” But I don’t suddenly feel the time clock going “T-minus 2 weeks till I need a job before I go crazy.” I’m very content to have a little bit of vacation time.

Two more questions: What is the best piece of advice someone gave you regarding acting? And what is your advice to actors?

For the business I think—and my current situation is a perfect example—it’s a long, long game. I remember coming out ofJuilliard thinking that it was a series of sprints, that you would look to your left and your right, and you’d see people in your class and you’d see people with the agents that you want, or you’d see them get job you thought you should have, or you weren’t booking and you tended to make an assessment of how you were doing by the people around you. And you judge that on very short sprints.

But the business is a marathon. Your career is a marathon, and you have to figure out how to pace yourself, and you have to figure out how to have a sense of inner worth and inner measure, rather than constantly looking around you. I look at the people in my class, certain people sprinted ahead and then fell back and haven’t worked in a while. And we’re all going through the same thing. There’s enough work for all of us. We’re not in competition with each other really. I know that’s sort of “self-helpy” speak, but it’s kind of true in this profession. There’s going to be a job that opens up for you because you didn’t get the other job. There’s enough work if you stay in it. There’s a huge attrition rate in this business because people can’t figure out how to go the whole way. It’s such a hard business and people fall off, and if you can figure out how to support yourself and feel good about yourself, your time will come. Your chance to get those things will come. Somebody told me that and in the beginning right when I came out of school I totally didn’t believe it. I was miserable for a lot of time, because I thought “If I hear another person tell me that I’m going to really start working in my mid-thirties, I’m going to just kill myself.” [LAUGHTER] I was twenty-something, and I thought “I want to do that!” and they’re like “Yeah, you know what? You’re going to have a great career in your mid-thirties and your forties and fifties.” That’s not what you want to hear that. You want to hear that you’re going to get it now. But looking back, I’m like, “Wow, that’s great advice.” It’s hard advice to take when you’re in the middle of it, but—if you’d have told me in my twenties that I’d be sitting with a Tony nomination for a new play, I would‘ve have believed it.

In terms of craft, I’d have to think about that. Tell the truth.

I’ll think of something good at some point. [LAUGHTER] I’ll give you a call at 2:00 in the morning when I can actually come up with something [LAUGHTER]